QIN TECHNOLOGY

ROADS AND CANALS

With the establishment of the Qin empire, roads and canals gained great importance. They were not only important locally but on an empire-wide scale.

Facts and Figures

Facts and Figures

The emperor built a network of post roads with the capital as its centre. The roads were 30 paces wide, built on raised beds and lined with pine trees planted at set intervals. He also built a highway 700 kilometres north to Baotou in Inner Mongolia to be able to move troops there quickly to fight the Huns. He also decreed that all carts and chariots had to have a standard, 6 foot wide, axle width so that the roads would not be damaged.

He built or improved many canals and established boat building berths both on the coast of China and on the main inland waterways. Ships which could carry up to 50 or 60 tons of material were built in these shipyards.

Roads and canals which were established during the Qin period remain in use today. This canal is down river from the irrigation system at Dujiang. In the foreground are "water" or, fresh fish ponds, near Chengdu.

Between 220 BC and his death in 210 BC Shi Huangdi made five inspection tours of the empire. He inspected his officials, issued decrees, offered sacrifices at specially chosen sites and marked his control over the territories by erecting stone monuments (called "steles" [pronounced steels] at various locations.

On his first tour he travelled around the lands of the Kingdom of Qin but, on his second in 219 BC, he went through his conquered lands of the six states and raised steles praising the Qin. This is one of the oldest steles known to exist. It is so old that it has on it's top part a style of Chinese characters which very few people can read today. This one is housed in the Forest of Steles Museum in Xian. These were the first books in that they recorded what was known about an event or person and could be read to remind people.

The Great Wall

The Great Wall disappearing across the mountains north of Beijing at Badaling. This wall is a modern rebuilding of the Ming wall which, in turn, had been built on top of Qin and Han foundations

This is one of the towers on the rebuilt Badaling Section of the Great Wall north of Beijing. Although this is a modern recreation, it, nevertheless, is a very good copy of what we know the wall looked like originally. Most parts of the Wall are, today, little more than a mound on the ground as the stones have been removed by local people to build their houses. Once the northerners, Xiongnu, Mongols, Huns, call them by whichever name you want to, overran China there was no need for the wall so it was not maintained, particularly out in the far west. as shown below.

The Irrigation System at Dujiangyan near Chengdu

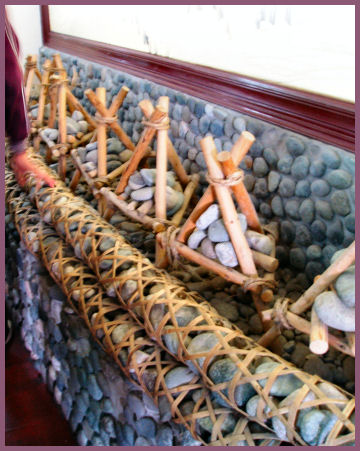

The Minjiang River, near Chengdu, was constantly subject to flooding and destroyed whole villages and good farming land. During the reign of the emperor's father as King of Qin, Li Bing, an hydraulic engineer, began the construction of a weir at Dujiangyan. The main part of the construction is the "fishmouth" which divides the river into two parts. On the one side is the main stream of water. On the other, water passes over a shallow weir and into canals. By passing the water over the weir the canals do not silt up and by letting most of the volume of water go down the main channel, farmers down stream do not miss out on the benefits of the water.

Did you know?

Did you know?

This system continues to work today, more than 2000 years later.

|

Dujiangyan "fishmouth" weir built during the Qin period and still providing protection from siltation whilst allowing water to flow into canals for irrigation, Guanxian County, near Chengdu, Sichuan Province |

|---|---|

| Detail of how the weir and the walls were built at Dujiangyan using different sizes of bamboo to provide (1) a framework to support heavy stones, and (2) light, flexible bamboo to wrap stones in to provide a solid base for construction, Guanxian County, near Chengdu, Sichuan Province |  |

Iron Tools to improve farming

A bronze pick head from the early Qin period, held in the

|

|

|---|---|

|

On the left is a modern recreation of a plough from the Qin period. This particular one shows a seed delivery box on top and iron facing on the wooden points. This particular artefact is at the Henan Provincial Museum, Zhengzhou Below is a bronze ploughshare from the Shaanxi Museum, Xian. It is 35 cm high, 32 cm wide and 10 cm thick. |

This is a bronze saw from the early Qin period held in the Shaanxi Provincial Museum, Xian |

|

Weapons and Armour

Although there was no standing army it is obvious from these weapons and the armour shown on the Terracotta Warriors that there was great organisation in putting weapons together. This meant that there was excellent centralised organisation as well as it required a great deal of co-ordination from mining, through to manufacturing, to collection and through to distribution.

|

Bronze knives from the early Qin period, held in the Shaanxi Museum, Xian. The knives would have had rope wrapped around the handle to help with the grip. They were used in hand to hand fighting. | |

|---|---|---|

|

On the left are Bronze arrows from Qin Shihuangdi's tomb, held in the Shaanxi Provincial Museum, Xian On the right is a compound bow recently recreated from a design found in the tomb of Shihuangdi, held in the Shaanx Provincial Museum, Xian |

|

Part of the Terracotta Warriors buried in Pit 1 at the Tomb of Qin Shihuangdi, Mt. Li. Each warrior's body is slightly different in stance, head, uniform and facial features. Many of the warriors were holding weapons when they were buried but they have since been removed during the time of revolt which followed the Emperor's death, or have rotted away over the past 2000 years. However, enough remained to tell archaeologists and historians a great deal about Qin times.

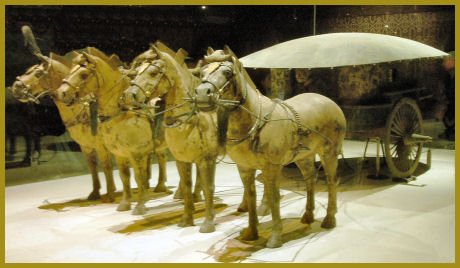

Terracotta horses were also made and buried in Shihuangdi's Mausoleum and remnants of their harnesses, saddles and other equipment remain in the pits for archaeologists and historians to examine.

|

||

This carriage is known as the number 1 carriage at the Terracotta Warrior Museum. It is made of 3064 gold, silver and bronze components. It is a model of a carriage used to clear the way for the Emperor when he was travelling around his empire. It has been built to half life size. It was excavated in another part of the tomb area away from the terracotta army and many other specialty items were found there, most of them made of gold and precious metals. Carriage number 2, below, is the one in which the Emperor travelled. It has a space for the driver and a cabin for the emperor to sit in.

|

|---|

|

Astronomy and Science

There was a great interest in Astronomy and understanding the Heavens mainly for magical purposes rather than scientific.

The emperor believed that the best way to site buildings was with the main door facing south so he had all his major buildings built this way. He could do so because the Chinese had already invented the compass using lodestone. They called it "the south-governor". However, the emperor took it one step further. He lined the gateway to his palace at Apang with magnetite so that no-one could enter with hidden iron weapons. He was not particularly interested in the science behind it but he appreciated the chance to use the "magic" to make sure he was safe.